Many people consider Hamlet to be the best play Western literature has produced. The play is praised for its philosophy, for the beauty of Hamlet's soliloquies, and great debates surround issues of Hamlet's madness, his action or inaction, and his sifting illusion from reality. Why, then, do we choose to de-emphasize these elements in presenting Hamlet: Reframed, to cut the soliloquies and the philosophizing?

The question is almost an answer in and of itself. Because Hamlet is so familiar (even those not acquainted with the play itself will discover nearly half the phrases in it have become modern adages). Because we already know the character of Hamlet so intimately. Because the same questions have been asked by each successive generation (and the answers have not changed much in 400 years).

It is as easy for some to consider the play dead as it is for others to put it on a pedestal.

We choose neither.

We cannot view Hamlet as a sacred work, infallible and untouchable. On the other hand, the play has life in it. Much of the world of Hamlet is often overlooked, or at least overshadowed by the complexity of the title character, and by the poetry he utters.

The Frame

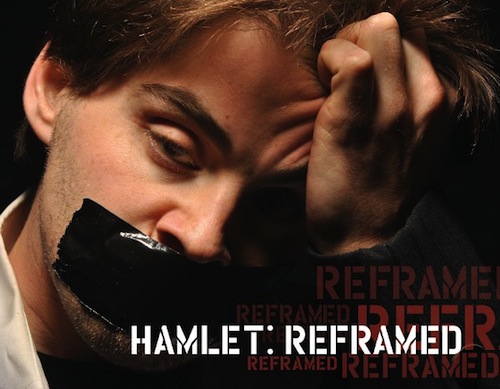

Sam Rabinovitz as Hamlet

The play of Hamlet, not surprisingly, follows the character of Hamlet. It is told almost entirely from his point of view, to the extent that the whole play feels like it is Hamlet's fantasy version of his own story. When reading or seeing the play, we all acknowledge this on some level. We realize that this is not how real events play out: that restless ghosts don't send sons after uncles, that the avenging brother doesn't just happen to return carrying a vial of poison, that the entire leadership of a country does not all die within minutes of each other, wrapping up a dynasty neatly (if bloodily). But we accept these leaps of the imagination because we go along with Hamlet. We see his story through his glazed eyes. And we have for centuries.

The Reframe

For that reason, Hamlet is tired. Many productions seem to be vanity projects - actors or directors wanting to tackle this great play, offering their drop of creativity to the sea of Hamlet exploration. But does that serve the audience? Does seeing one more slightly different, slightly new take on the same character provide an audience with a fresh view of the play, themselves, or their own world?

What if no one saw this?

The film of Hamlet starring David Tennant does some of this, and provided the point of departure for our reframing. Among other things, it wonderfully depicts Denmark as a surveillance state. Even when Hamlet is alone in the room, CCTV cameras are on him, and we imagine Claudius and Polonius watching his every move from a control room at the heart of Elsinore. It begged the question: what if the cameras were turned off?

We wouldn't see Hamlet rationalizing his every decision. We would not see him ponder the meanings of life and death. We would not see him encounter the ghost of his father, which launches him on his vengeful crusade. Instead we see him suspiciously greet his visiting friends, brutally break up with his girlfriend, kill one of Denmark's top advisers, and get sent to England because his behavior doesn't suit a prince.

So we leave the frame of Hamlet, but find we need an anchor, a new perspective. Something more objective. Our frame asks: if the audience were members of the court, even one fairly close to the action, but not privy to everything, what story would that be?

It turns out there is quite a bit left in Hamlet, once you take away the prince of Denmark (or his perspective). A newly wed king and queen. A prince who is unhappy about something, but we're not quite sure what. An impending invasion from Norway. The "kitchen of politics" (to borrow a phrase from Anouilh's Antigone, which also depicts family conflict affecting an already unstable nation). Shakespeare offers so much to the world of Elsinore that is overlooked (or cut) in most productions.

Not Shakespeare's Hamlet

We are not producing Shakespeare's Hamlet, which is Hamlet's Hamlet. We are mining the text for different ore, and producing Elsinore's Hamlet. We offer a new perspective to the events of the play, one in which the affairs of state are the primary concern, and Hamlet increasingly becomes a threat to the well-being of the nation.

One major result of the change in perspective is how we portray Claudius and Gertrude. In Hamlet's mind, his mother Gertrude is a horny old woman, and his uncle/step-father Claudius is a cartoon villain, little more than a Snidely Whiplash. In our production, we see this point of view in 'The Mousetrap,' the play Hamlet has commissioned for the king and queen to see. However, where the play-within-the-play serves to drive home the point of fratricide/regicide in Shakespeare's version (and "catch the conscience of the king"), in our Reframed, it shows the stark contrast between who the king and queen are, and what Hamlet thinks of them.

Claudius (John Stange) and Gertrude (Sara Bickler)

get news from Voltimand (Pamela H. Leahigh)

Our Claudius is a king who's rolled up his sleeves and gotten to work, trying to repair the country after decades of his brother, Hamlet's father, acting selfishly rather than governing in the best interest of the state. Claudius is a practical man, politically savvy, charming, and on top of the business at hand - all in all, a good king. We have not changed the fact that he killed his brother (with good reason in our case), but because it's not a fact the court would know explicitly, it hardly comes up in our cutting.

Gertrude, more than anybody, wants what is best for the state, and what's best for her son. She is the daughter of a Danish king (we went back to the original source material, where Hamlet Sr. and Claudius marry into royalty), and intimately concerned with the nation's well being - it's her family's legacy and responsibility. She has crowned Claudius instead of Hamlet not out of lust, but because Hamlet is not ready to rule. She knows that if Hamlet takes the throne, he is being set up for failure. Along with needing to clean up Hamlet Sr's mess, his death has motivated Prince Fortinbras of Norway to invade Denmark. This is not time for a teenager to take charge. Claudius, who has been involved with Danish politics for years, has a better resume. Instead, they name Hamlet as Claudius' successor, and ask him to remain in Denmark, at the heart of the government, and learn the craft of leadership.

Shakespeare has woven a beautiful and subtle tapestry of family and political drama that in most productions, hangs in the background. In reframing Hamlet, we explore this unstable political world and what effects an unstable prince have on it.

The new Denmark

Gertrude (Sara Bickler), Claudius (John Stange), and Hamlet (Sam Rabinovitz)